A proof of concept allows teams to solve a problem or explore an opportunity at a small scale before investing significant time and resources into a major project. By performing a proof of concept experiment, you can make mistakes, find pain points, and develop best practices without any major real-world risks.

In my experience, a proof of concept (sometimes called a pilot) can often mean the difference between failing to effectively lead a project and successfully implementing an efficient and effective plan. In this article, I’ll share some of my secrets to successful project execution, focusing on running small proof of concepts, pilots, and experiments.

What is Proof of Concept?

A proof of concept (POC) is a series of activities intended to demonstrate the potential effectiveness of an early stage project, change, business idea, or product idea. They can help validate the potential success of a project, especially in cases where what is being attempted is new or novel, such as the creation of new products, technologies, and services, or changing processes.

In essence, the POC proves that a project can work at a small-scale and provides a small data set that project leaders can then use to further iterate on their project plan to increase the likelihood of success for the larger-scale project.

What Is The Purpose Of a Proof Of Concept?

Running a POC helps support long-term project success by identifying issues early, which minimizes risks for the full-scale implementation and may even reduce costs. It can also help build stakeholder engagement and confidence because they got to see the idea work on a smaller scale before they sign off on a large-scale implementation.

For project managers, completing a proof of concept can also greatly assist further stages of the project because POCs allow for data collection and experimentation specific to the project initiative, allowing them to learn about project's strengths and weaknesses before investing in a large-scale project.

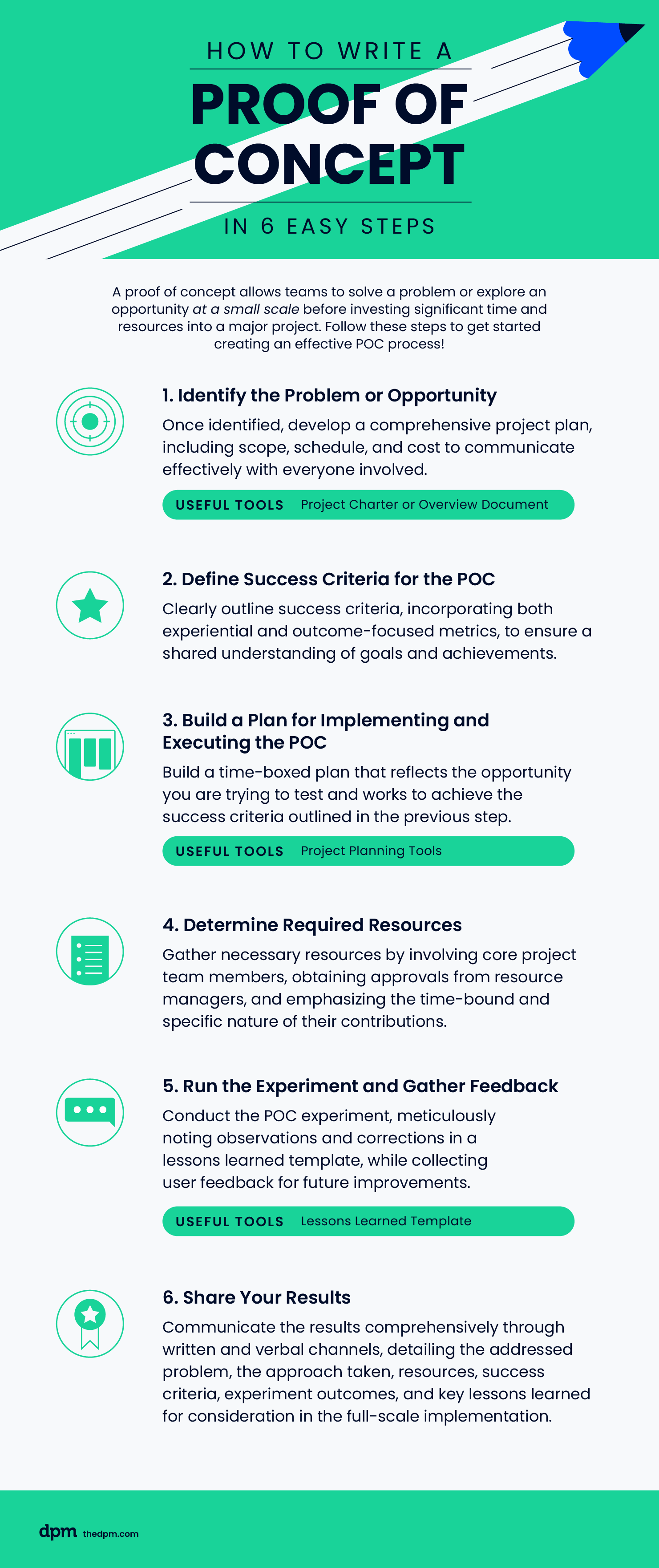

How To Write A Proof Of Concept

Proof of concepts can happen within an existing project or might be a standalone project on their own, depending on how the development of the concept has been progressing thus far.

Either way, when planning and executing a proof of concept, follow these steps to get started creating an effective POC process!

1. Identify the Problem or Opportunity

The first step in planning a proof of concept is identifying what it is that you want to try or test. Build the beginnings of a project plan, including scope, schedule, and cost.

When getting started in this step, I like to go for a full-on project charter or overview document to share with anyone and everyone that will be related to or working on the project and POC. Remember, just because a POC is smaller than a full-scale implementation doesn’t mean people don’t need thorough communication about it.

2. Define Success Criteria for the POC

Once you have the problem to solve and you have an approach you want to test, it’s critical that you define success criteria for the POC. Defining success criteria will help everyone understand what you are trying to achieve and when, because the metrics for a successful proof of concept is detailed in the success criteria.

Success criteria can be both experiential and outcome-focused. For example, your success criteria could include identifying if a new process can work on a small scale, or it might simply involve gathering five key takeaways from the experience to inform the next steps in project development.

3. Build a Plan for Implementing and Executing the POC

Once you have an idea of what you are trying to accomplish and how the success of the POC will be measured, it’s time to build a plan that reflects the opportunity you are trying to test and works to achieve the success criteria outlined in the previous step. If you need help building your plan, there are numerous project planning tools that you can use to create an efficient workflow.

The plan for implementation and execution must be time-boxed and must be a representative sample or test for what could be implemented at larger scale to address the problem or opportunity identified.

4. Determine Required Resources

Once your plan is defined, you’ll need to gather the required resources. Work with your core project team members to figure out who needs to be involved, then work with the various resource managers, development teams, and others within your organization to gain approval for folks to be involved.

When talking to managers, I often talk about testing a new idea, finding out if something will work, and the opportunity for them or one of the people on their teams to be included in ensuring the solution works for their part of the organization. I've also found that it is easier to get commitment from managers across an organization when the ask is time-bound and specific.

5. Run the Experiment and Gather Feedback!

The next step in your POC journey is to run the experiment! Pay close attention to everything as it gets started. Remember, this is a test, so anything you observe, correct, nudge, or support along the way should be noted in a lessons learned template so that you have as much data as possible to apply to the full implementation.

When the POC ends, celebrate the involvement of all resources and teams as you collect user feedback and lessons learned to be incorporated into your results and project plan for the full-scale implementation of the final product.

6. Share Your Results

Finally, once your POC has concluded and feedback is gathered and organized, it’s time to share the results of your POC experiment with project stakeholders, sponsors, and interested parties. I would recommend that you communicate both on paper and in meetings to ensure that your information reaches the people that need it in ways that will maximize their understanding.

Share about the problem you tried to address, how you went about it, what resources you engaged, the success criteria for the experiment, how the experiment went, and what lessons learned you gathered.

Proof Of Concept Examples

Here are a few examples of proof of concepts at work in various disciplines.

1. Software Engineering

Proof of concept practices is exceptionally common across STEM. In software engineering, proof of concepts is implemented to validate the need for new systems or services.

New software startups often produce a pre-production version of their app to have a select population give it a try and provide feedback—this is a proof of concept!

2. Product Development

In product development, proof of concepts might include testing new material for apparel.

Nike is famous for their various proof of concepts over the years, starting from the famous waffle sole running shoe, and later moving on to developing new materials such as Flyknit and even integrating running shoe sole surfaces with prosthetic legs for runners.

3. Television Production

In television production, TV series often produce a pilot episode at the first initial episode to get feedback from and to validate that the concept, actors, and topics are relevant and important to viewers.

These pilot episodes often become the first episode of the series, and this is often the reason that some pilot or first episodes feel so different from the following episodes; some even have different characters or actors!

4. Pharmaceuticals

In pharmaceutical development, proof of concept processes are carried out through pilot studies, and various levels of clinical drug trials. These processes give feedback to the drug creators which helps them to create a safer, more effective drug for the masses!

5. Process Change

One of my favorite examples of running a proof of concept on a process change was for a project I led at a large software company. We ramped up hiring in 2020 and 2021 and needed to completely change the way we executed onboarding.

Instead of overhauling everything at once, we created a small team to define and build a proof of concept, a new process that was used on a few specific new hires. What we learned was so incredibly valuable that we were able to shift the way we were thinking about the process entirely, leading to a much better long-term outcome that was more sustainable, more automated, and produced a better result.

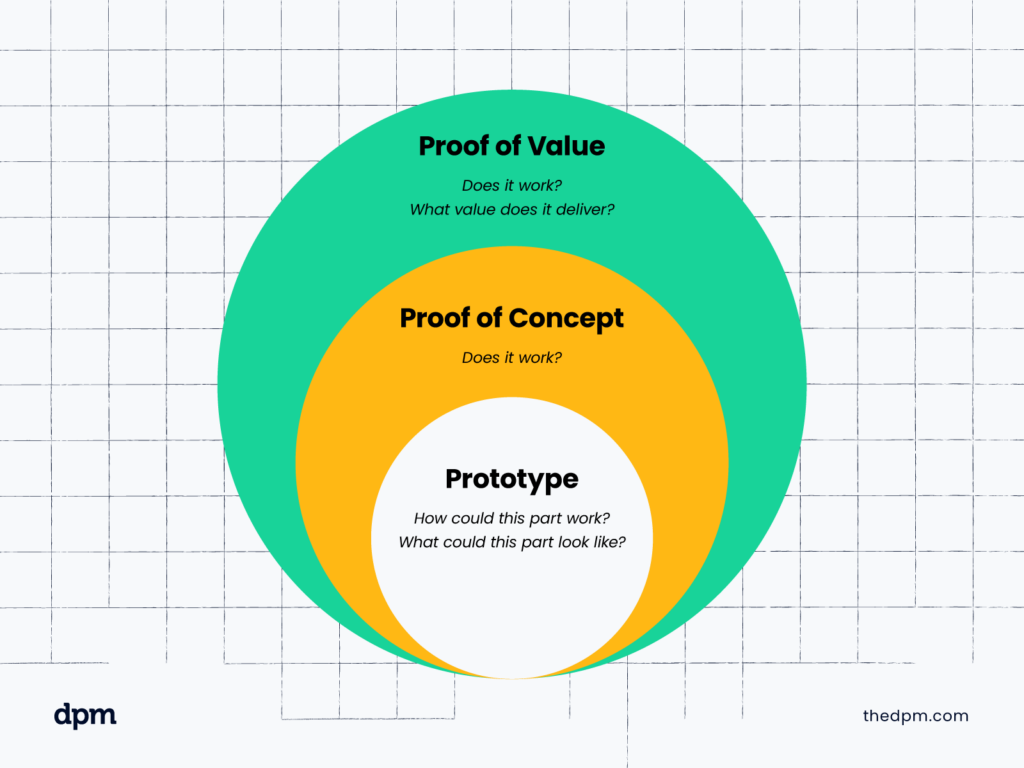

Proof of Concept vs Proof of Value

While a proof of concept is intended to demonstrate the feasibility of a concept, project idea, or change, a proof of value goes further to quantify the impact and benefits of the proposed solution.

In a proof of value, not only is feasibility tested, but the value of the change is measured, enabling quantitative analysis of the project’s intended outcomes.

Let’s compare the two:

| Proof of Concept | Proof of Value |

|---|---|

| Does it work? | Does it deliver value? If so, how much? |

Proof of Concept vs Prototype

Prototypes are early physical or digital iterations, versions, or representations of a potential solution or tool. Prototypes are often found in software development (where they are also called wireframes) or the product development process.

Similar to a proof of concept, a prototype tries to demonstrate how something could work but is not required to actually work in a test. Prototypes are most often seen in product creation, both physical and digital products.

In contrast, a proof of concept is a bigger initiative than a prototype and looks to demonstrate the viability of the project or change.

| Proof of Concept | Prototype |

|---|---|

| Does it work? | How could this part work? |

| What could this part look like? |

Getting Started On Your POC

As you get started planning your proof of concept, don’t forget to stick to the project management basics of planning, communication, documentation, and collaboration.

Many of the principles of full-scale project management apply to a POC, just at a smaller scale and hopefully in a shorter time.

Next, and as usual, please consider subscribing to The Digital Project Manager newsletter so articles like this and more are delivered to you, hopefully when you need them most!