Throughout my time as a developer and a , I’ve found myself experimenting with a number of different strategies for defending my ‘s decisions and convincing clients to go along with our vision. When I began this journey, harnessing a reliable method for this seemed a little like black magic. I’m an ambivert and this task seemed better suited for an A-type, gift-of-gab person. With time I’ve realized it just takes time and careful consideration.

The approach I now use is producing positive results. To save others the trouble, I thought I’d share the insights and discoveries from my experiments on .

First, Let’s Talk About Doubt

Clients and stakeholders invariably want all of their expectations met. They’re not only making a sizable financial investment for the proof of concept, but stakeholders’ names are also on the line. The attachment for many stakeholders is personal – they see the delivered as a measure of their performance.

When a ‘s preferences aren’t met, doubt starts to rear its ugly head throughout your . And in the context of a high-profile , this doubt can be the first step towards the demise of an otherwise healthy relationship.

Doubt can kill any positive or healthy relationship that you have previously built with the stakeholder.

Notice I used the word “preferences”, not “expectations”. Why? Because preferences are subjective, and though users are individually subjective, numbers and user data are not.

So let’s go ahead and explore a few different levels of how to say “no” to your and get them on side with your ‘s vision.

Experiment 1: Blunt Argumentation

Probably the most straightforward way to say no is to… well, just say no. I know many PMs who see themselves as one side of an adversarial process – the defender of their and of their organization. Their strategy is literally to play hardball: say no, and hold your ground.

My experience is that the result generally isn’t positive – either it’s a won battle in a -long war between and PM, or it’s a bullying situation where the PM wears a down into submission, leaving behind resentment and that sense of disappointment.

I’ve tried this strategy, and honestly, it’s not for me. So I tried a different approach.

Experiment 2: Dogmatism

Something that did have a better effect for me was a more dogmatic approach: using trends and the opinions of vocal thought leaders as “proof” that my ‘s position was sound. Rather than simply shut down clients’ ideas, we would invest the time to share some of the writings out there advocating for the approach we were recommending.

This got us closer to evidence-driven decision-making, but our “proof” didn’t have the adoption yet to measure success. Likewise, we hadn’t had the time to really evaluate the new method ourselves. And as much as it helped me be persuasive, it didn’t help build our ‘s understanding of their specific needs and challenges. In fact, it often kept them on the outside.

Experiment 3: Data-Based Decision Making

What finally started working for us as a was shifting the focus from the subjective to the objective and measurable. By doing so, we could make calculated decisions that our could see and understand. Making decisions based on a shared understanding then helped us avoid disappointment from unmatched expectations .

But it did something else: it built trust.

By opening the discussion to our clients, reviewing progress with them, and providing context on the ‘s performance, we opened the door to building our ‘s confidence in the as well as a shared understanding of the problem set.

Along the way, we measured progress against our fixed constraints at appropriate intervals. We explained how adjusting the flexible constraints and requirements can affect the product’s feature set and overall quality. We included the as part of the decision-making , and shared our process for deciding their highest-value requirements.

Admittedly, this was a bit clumsy at first, but it quickly translated into an increased feeling of control and ownership of the . It also armed them to go on to explain to other stakeholders some of the value-rich features and attributes that may otherwise have gone unnoticed.

This is now my preferred method for nixing any or that doesn’t provide value. Of course, sometimes the gets fixed on something you know won’t provide value. However, explaining a process of objective decision making will help build trust and often, you won’t have to say no; they make the decision themselves.

How To Do It

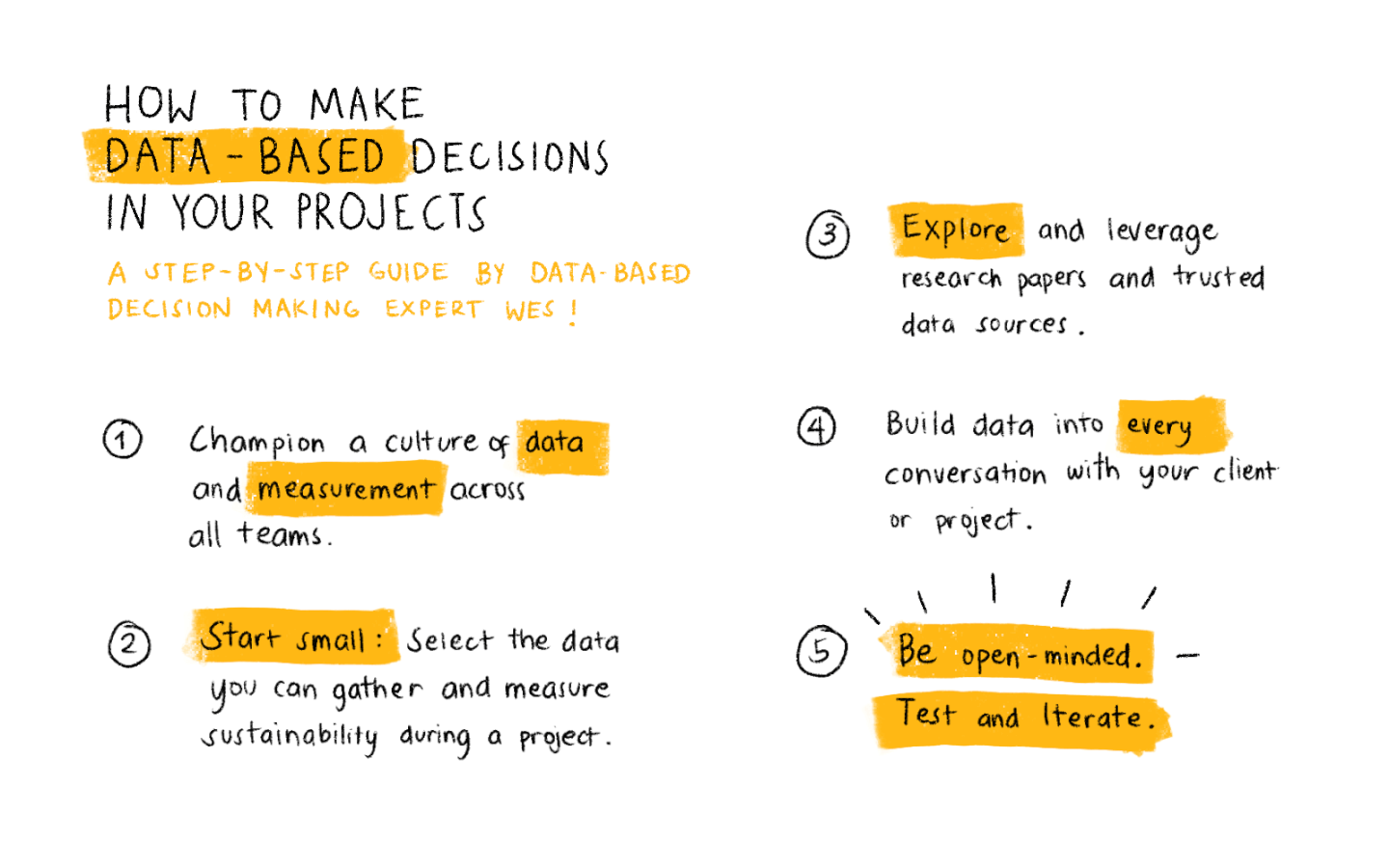

Making data-based decisions is a simple 5 step process.

Okay, so getting to data-based decision making in our projects wasn’t turnkey. For anyone in the process of making this transition, here’s what I would recommend:

1. Champion A Culture Of Data And Measurement Across All Teams.

Yes, that’s a loaded statement, but it can start with just the desire for each team to have some kind of methodical approach and evidence-based rationale for doing things.

2. Start Small: Select The Data You Can Gather And Measure Sustainability During A Project.

Your projects won’t have a big data engine with machine learning right off the bat. Use an MVP mentality to build a data framework that is meaningful and viable.

3. Explore And Leverage Research Papers And Trusted Data Sources.

Secondary sources such as research papers, reports, and open data can augment areas where you don’t have data of your own.

4. Build Data Into Every Conversation With Your Client Or Project Sponsor.

You’ll also need to build a culture of data within your or . Use every opportunity to tilt their mindset towards data-driven decisions rather than subjective preferences.

5. Be Open-Minded. Test And Iterate.

There’s no silver bullet. What works well for one may not at all for other projects. Keep a playbook of your process and continue to test and iterate.

Things To Be Wary Of

I’d be remiss not to mention that having all the data doesn’t mean it’s going to be smooth sailing from there. Whereas you may be able to use data to figure out what a really needs versus what they say they want, if the data doesn’t reflect well on them or goes against their original vision, you can run up against resistance, inadvertently build animosity, or your efforts might just get ignored.

The thing to consider with data and its delivery is the human component. From a psychological standpoint, sharing data and driving that conversation still requires tact, sensitivity, and professionalism.

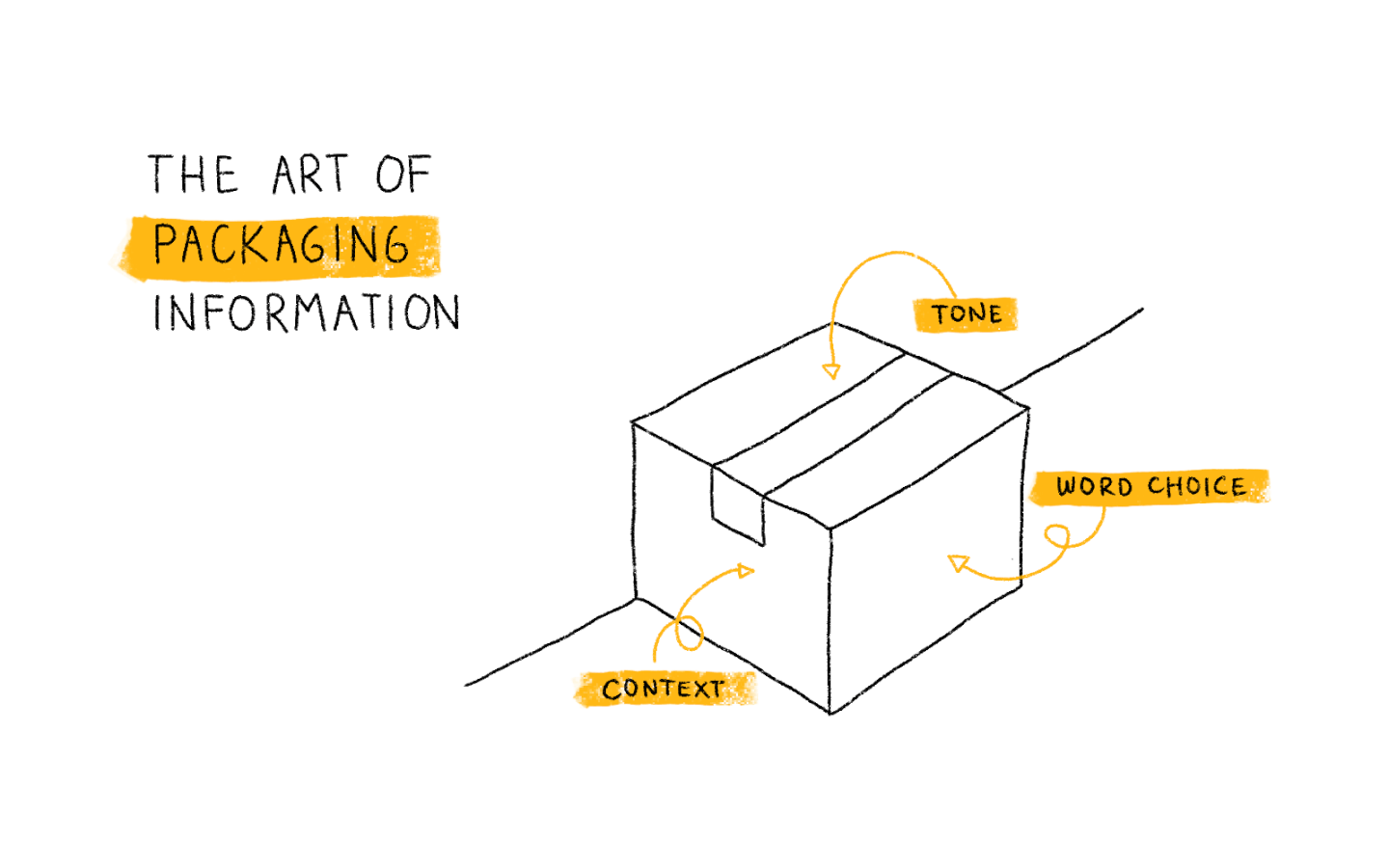

It’s important to properly package the information you provide to stakeholders in order to build trust and keep up a good rapport.

Part of the art is packaging the information in such a way that it will be heard and considered. Some elements that factor into that include:

- Context: plan when and where to have the conversation. Some data is better-prefaced one-to-one before being discussed in front of your team or your client’s team.

- Word choice: practice using words that frame the data neutrally, and avoid using words that can be construed as abrasive or confrontational. Here are some examples of what I mean:

- Things to avoid

- “The data says…”

- “It’s clear that…”

- “Everyone is able to identify…”

- “It’s obvious that…’

- Things to use

- “It looks like the data is suggesting…”

- “Based on users’ preferences over the last 30 days… “

- “I wonder how users might respond to this feature”

- Tone: make a strong recommendation, but try to provide options that keep your influential stakeholders and sponsors in the driver’s seat. Just make sure they’re aware of the consequences of their decisions!

What Do You Think?

For me, including the as part of the decision-making and sharing our process for deciding their highest-value requirements has increased their feeling of control and ownership of the . Sharing the idea of intelligence-based design has also helped build my clients’ confidence in my , knowing that they’re working methodically rather than just on a whim.

But, again, this is just my journey, which I am perhaps just at the beginning of. What do you think? Do you think these tips could be useful or effective for you? What other advice would you give to digital managers trying to leverage data-based decision making with their teams and their clients? Let me know in the comments!

Here's a list of tools to help you stay on top of everything you're managing so you can make better decisions: 10 Best Desktop Project Management Software